The East Devon Pebblebed Heaths comprise a number of adjacent Commons, including those of Dalditch, Withycombe, Lympstone, East Budleigh, Bicton, Woodbury, Colaton Raleigh, Hawkerland, Aylesbeare and Harpford. The core area (excluding Lympstone, Withycombe and Venn Ottery Commons) is owned by Clinton Devon Estates and managed by the Pebblebed Heaths Conservation Trust.

A ‘Common’ is typically characterised by the customary rights of use (commons rights), historically associated with the inhabitants (i.e. ‘the commoners’) of particular properties that are adjacent to common land. Historically, these rights included the right to graze domestic stock and collect wood for fuel. Few legitimate commons rights were being exercised on any of the Pebblebed Heaths by the time of the Tithe Maps between 1839 and 1846. However, grazing did continue at least until the Second World War, possibly on a tenant basis. The Commons Registration Act (1965) recognises one commoner who still retains the right to graze either two horses and two cows or two horses and twelve sheep in Woodbury and Colaton Raleigh Common.

Because of their long history of occupation and use, the Pebblebed Heaths have a rich archaeological history, with over 168 historic features noted in the County Council’s Historic Environment Record.

From the prehistoric peoples who built the large number of barrows and cairns on the heaths, to the military use of the heathlands during World War 2, the footprint of human occupation is evident at every turn.

Perhaps the most important archaeological site is Woodbury Castle – one of the most well-known archaeological monuments in all of Devon. The Castle is an Iron Age hillfort, with its impressive ramparts and ditch echoing back to an ancient era upon the heath. Due to its historical interest, Woodbury Castle is designated a Scheduled Monument (SAM No. DV61).

The Pebblebed Heaths are defined by two primary distinct vegetation types: dry heath and wet heath. Dry heath typically occurs on slopes and better drained areas, with wet heath in valley bottoms associated with streams, water table flushes or where the land is poorly drained. Although these two broad and locally variable vegetation types define the Pebblebed Heaths, over 37 different plant communities have been recorded, including those associated with woodland, mire and bracken.

Although individual dry heath communities can typically be species poor, over 605 vascular plant species, 378 species of fungi and 1,390 mosses and liverworts have been found on the heaths. This includes 94 of county, national or international significance.

Please read our Biodiversity Audit for further information about the vegetation and plant life that occurs on the Pebblebed Heaths.

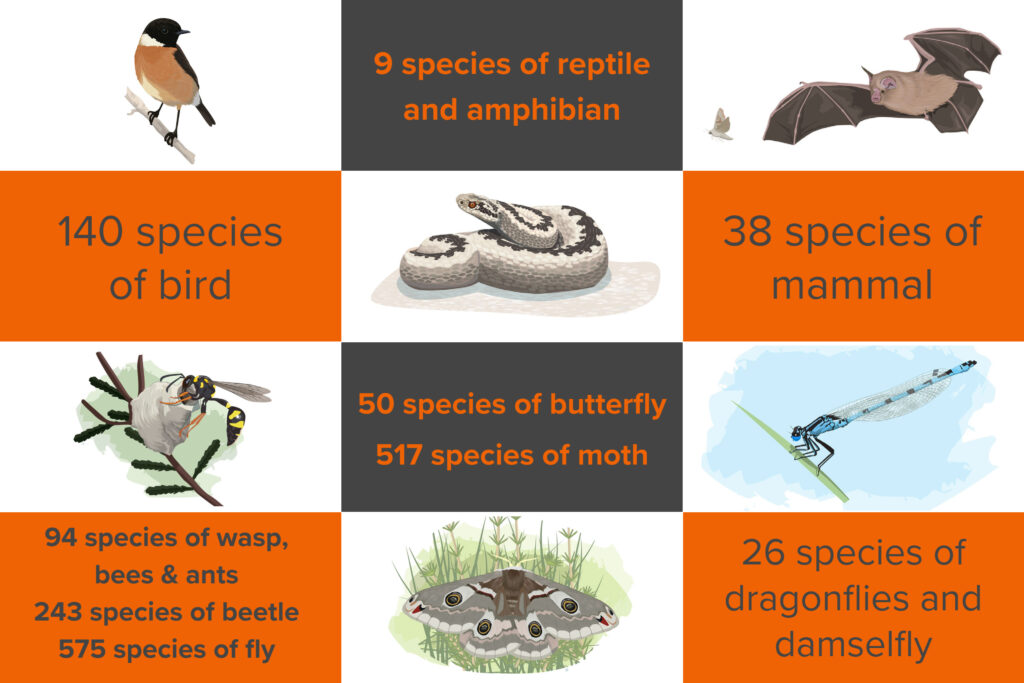

The Pebblebed Heaths offer a haven for wildlife, supporting over 3,000 species, including many which are rare or threatened. You can read more in our Biodiversity Audit.

One of the most iconic and rare birds to look out for is the Dartford warbler. These little birds are heathland specialists and can be seen across the whole area of the Pebblebed Heaths but particularly like to nest in the dense gorse where they forage for insects. Unlike most warblers they live here all year round though are most visible in the spring breeding season, when the males can be heard defending their territory. During the summer you may be lucky to see the young flying amongst the heather and gorse, on a good breeding year a pair may raise up to three broods of chicks.

One of the most iconic and rare birds to look out for is the Dartford warbler. These little birds are heathland specialists and can be seen across the whole area of the Pebblebed Heaths but particularly like to nest in the dense gorse where they forage for insects. Unlike most warblers they live here all year round though are most visible in the spring breeding season, when the males can be heard defending their territory. During the summer you may be lucky to see the young flying amongst the heather and gorse, on a good breeding year a pair may raise up to three broods of chicks.

The mysterious nightjar is one of the special birds that can be found on the heaths. This unusual-looking bird is perfectly camouflaged and resembles the bark of a tree. The nightjar’s diet is made up of flying insects, including moths and beetles. It is nocturnal and spends its nights hunting for food, catching it on the wing thanks to its wide mouth and silent flight.

Males have bright white patches on the tips of their wings and tail which they flash when displaying to other males and females, their enigmatic ‘churr’ call is the twilight soundtrack to the summer. They do not build a nest, instead laying eggs directly on the ground, where their bark-like camouflage comes in to its own. Nightjars arrive from Africa during the spring, usually around April-May and after the summer breeding season on the heaths migrate back south during September.

One of our rarest species, the Southern Damselfly, can be found living in small channels, or ‘runnels’, in the black bog rush mires on the Pebblebed Heaths. This highly specialised species needs the conditions to be just right in order to thrive, they can be helped by the largest animal to be found on the heaths, our grazing cattle. The grazing and trampling of the cattle keeps the vegetation in check and the runnels open so that the damselfly can complete all the stages of its lifecycle, most of which it spends as larvae in the water rather than flying as an adult.

The silver studded blue is a small butterfly which can be seen flying from June until August. It is a rare heathland specialist, generally found in areas of heath that have shorter vegetation and bare ground, where they form colonies. The teams that manage the Pebblebed Heaths carry out work each year to keep the plant growth in check to allow these butterflies to thrive.

The males are blue with a black border, while the females are far less easy to see being brown with a row of red spots. Both have small reflective ‘studs’ on the underside of their wing.

Silver studded blues have an amazing relationship with black ants. The caterpillars secrete a sweet substance that the ants feed on; in return the ants look after the caterpillars, tending them, carrying them around and protecting them from insect predators.Even newly-emerged adult butterflies are also often attended by the ants which give them some protection from predators.

They overwinter as tiny eggs which hatch in spring. The new caterpillars feed on the tenderest parts of their foodplants, which include heathers and gorse. The caterpillars grow through four stages, or ‘instars’, moulting between each stage. The caterpillars then pupate just below ground in early summer, often in an ants’ nest. When the adult butterflies emerge, they don’t spend much time visiting flowers to feed on nectar but, when they do, heather is a favourite.

The first formalised monitoring of wildlife on the Pebblebed Heaths was undertaken in the 1970s, with annual monitoring beginning in the late 1980s. All records are archived at the Devon Biodiversity Records Centre.

Key species for which data is recorded annually are the Dartford warbler, nightjar, curlew, stonechat, southern damselfly, silver-studded blue and reptiles.

The Pebblebed Heaths are amongst the most important conservation sites in Europe due to the rarity of the habitats and species found. The UK supports 58,000 hectares of lowland heath which represents about 20% of the European total. Approximately 25% of the UK’s lowland heaths are found in the south west (14,500 hectares), with 4,000 hectares in Devon. Covering over 1,400 hectares, the Pebblebed Heaths comprise the single biggest expanse of lowland heathland in Devon.

Declared a national nature reserve in 2020, the main core of the Pebblebed Heaths is notified as Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI). The site is also of international conservation value and is designated a Special Area of Conservation (SAC) and a Special Protection Area (SPA) under the EU Birds Directive and the EU Habitats Directive due to its support of rare habitats, nightjars, Dartford warblers and the southern damselfly. The East Devon Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB) was designated in 1963 and covers all of the Pebblebed Heaths. The AONB Management Strategy recognises the Pebblebed Heaths as a significant landscape feature in East Devon, containing important natural habitats and archaeological features.